|

Other alterations soon took place to the headstock as well. But as Matt Umanov states "The lower portion of the

peghead was already wide, and the tuning pegs already mostly in line with the nut slots, although that was not my

intention; I was thinking more in the realm or esthetics.. At that point, Danny may have lined the tuners up a little

more closely (but not much) with the nut slots, maybe he got a brainstorm on the spot."

The new headstock also brought the tuners closer together vertically, which made for a minimum of string tension

difference between strings. Altogether, the changes made for a radically new styled headstock with its new looks only

being surpassed by its functionality.

|

|

|

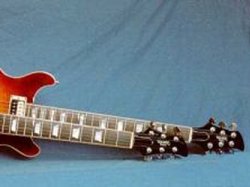

Ironically, it would not be Dan that would have to worry about a lawsuit over a headstock design - but as can be seen above left and right, it's

surprising that Dan didn't take issue with Hamer over some of their instruments. Probably because only two such instruments were

produced in 1978 & 79. They were custom built for the guitarists in the British rock band Rockpile.

|

|

Above left, both of the Hamer instruments made for Billy Bremner & Dave Edmunds of Rockpile. It is unknown why they both requested to have

Dan Armstrong styled headstocks on them. At upper right, even Guitar Hero models sport the Armstrong style headstock.

|

The maple neck features an adjustable steel truss rod

to reinforce itself by counteracting the pressure of the string pull, which in turn helps to keep the neck straight.

Bill Richardson goes on to say more. "Dan knew that many of his customers were greatly over-tightening the truss

rods on their guitar necks in order to get better string action, and he knew of the inherent danger of over tightening

the rod. So when it came time to design his own instruments, he built both the necks and fingerboards out of

quarter-sawn woods instead of the more available slab woods that is commonly used in the industry."

Photo courtesy of Bill Richardson.

|

Bill continues, stating "The biggest misconception players have is that truss rods are for adjusting action. While adjusting the

truss rod does indeed affect the playing action, that's a side effect and not the purpose for the adjustment. The

sole purpose of the truss rod is to straighten the neck, and while quarter-sawn wood was more expensive, the neck is

much stronger, much less likely to ever twist or warp and the pressure of the truss rod to keep the neck straight is

greatly reduced, perhaps by as much as 40% in some cases. Dan knew all this, and he said that he didn't want his necks

coming back in for repairs later on down the road so he used quarter-sawn woods throughout their years of production."

As seen above, luthier Bill Richardson works on a Dan Armstrong bass guitar that it's new owner had purchased and had

brought in to his shop for just such a repair. Apparently its past owner had kept tightening the truss rod instead of

making bridge height adjustments or placing a shim underneath the base of the neck to slightly change the angle of the

neck. As a result, the truss rod was tightened to the point that it broke. Bill goes on to say "on this bass the

truss rod was broken so the only thing to be done was to replace it. The only problem is that the past owner, in

addition to busting the truss rod, had used epoxy to glue the busted rod in what would be its final resting position."

The photo above shows the replacement truss rod "ready to install, but first I had to dig out the old glue and remove a

tiny bit of the formica just under the top truss rod cover screw to pull the old truss rod out. Then I tapped a new

one (like Dan told me) and rebuilt a new ivory nut for the customer and we were on our way to a killer bass again."

|

There really isn't a body heel, but a small change in the neck shape just prior to it getting squared off in order for it to fit into

the machined cavity of the acrylic body. The rosewood fingerboard rises above the maple neck by approx. ¼" at the center,

moving down to approx. half as much at the edges due to the 9.5° radius of the fingerboard itself.

Matt Umanov designed the tongue when building the necks for the prototypes, and describes it's origin stating "It's exactly the Les Paul

design of neck attachment, maybe with a slightly longer tongue, to accommodate bolts rather than glue." When it was completed, the

33/8" maple tongue extends deep into the body, and bolts down right next to the pickup which helps, not only

the sustain, but also the structural rigidity of the neck to body joint. The Dan Armstrong guitar was not the first instrument to feature a

deep-set bolt-on neck, as Mosrite had such a neck on their mid-60's

Ventura Mark V and other similar guitars in the early 1960's.

|

As such, the neck is a front bolt on design that fastens to the body using four ½" carriage bolts, and when secured in place, the maple

tongue rests flush with the top of the acrylic body with the fingerboard elevated slightly above it, which in turn allows access to all 24

frets. The two octave neck, though rare for its time was not a first. For example, the

1961 Burns-Vibra model has a 24 fret neck. Since the tongue resides underneath

the guitars' scratchplate the tongue features four partially recessed holes, larger in size than the holes for the ½" bolts, which allow

the washers and nuts for the aforementioned bolts to reside in and tighten the neck to the body.

The tongue of the neck is also where the end piece of the adjustable truss rod can seen. As seen above, notice the maple filler strips that are

glued in afterwards. The truss rod screws into this end piece and so is replaceable (if ever need be). The new truss rod has to be inserted from

the guitars headstock as seen at the top of this page.

The tongue sometimes features a letter, or letters that are stamped into the base, or bottom and it's most

unfortunate that Dan had passed away before I could ask him about these unusual markings, but I can't help but believe that

even he might not have had an answer as to what they were, or what they represented.

At upper left, one of my own necks - a very early 1969 model reveals the letter A stamped upside down

at the base of the tongue. At upper right, another model reveals the letter G also stamped upside

down at the base of the tongue. Notice how the tongue is not even drilled out for bolts to attach it to the body.

My best working theory was that perhaps only the earliest models featured these stamped in markings, though I still

didn't know why - but as can be seen at upper left, and with a serial number of D1025A - the tongue on this bass neck

has the letters G V stamped into it and is one of the first ever seen with two such letters. Like the

others however, these letters are stamped upside down (relative to the serial number and the rest of the neck) and is

more centered than the others which are stamped more toward one side.

At upper right, another very early model bass which can be seen more in the bass section. This one is such an early

model that its serial number is stamped into the base of the neck, rather than on the side like most. Notice how the

neck bolts do not have a machined end, but rather have been cut down (more about it in the hardware section). The

serial number of this neck D150A relates to around the 50th model to have left the actual production line

as Dan long ago told me that the first 100 were experimental models. Notice the larger letter A that

is stamped in just to the right of the serial number. This one is also unusual in that this letter is stamped in

right-side up. Given such an early serial number, and, coupled with my own neck which was the 104th model

to have left the production line and you can see where I developed my theory from. However, and as seen back at left,

the serial number D1025A corresponds to the 925th model off the production line, which tends to shoot

holes in this theory.

Despite my best efforts to make sense of it all, the only thing I can report to date is that I've noticed the earlier serial

numbers tend to feature the letter A while later models seem to have the letters G

and GV stamped into them. Most Dan Armstrong · Ampeg instruments do not even have

these additional letters stamped into the neck tongues, but as seen here a small handful of them do. Unless more

information is forthcoming in the future, it seems likely that this will forever remain a Dan Armstrong guitar mystery.

continue

menu

Names and images are TMand © Dan Armstrong / Ampeg. All rights reserved.

All other names and images are TMand © of their respective owners. All rights reserved.

|

| |